The internet is a physical thing. And it is responsible for around 4% of global emissions - more than the entire airline industry, and is growing by 5% each year. In an age when scientists are warning us that every bit of warming matters, it's time to get real about the impact of the digital world.

The biggest coal-powered machine on earth

So let’s start by looking at the hardware. Rare materials are needed to build computers, phones and tablets, and we keep upgrading our devices, sometimes as quickly as every two years. Beyond our personal devices, rare materials are also needed to build the huge servers hosted in data centres that store the inconceivable amount of data we create and use. To connect all these data centres are giant cables that criss-cross the planet.

To retrieve these rare materials, to build and connect these data centres, to lay the physical infrastructure for our digital networks, there’s a hefty environmental cost – mines are dug, natural habitats are disrupted and materials are transported.

More roads. More cars.

When governments attempt to reduce traffic by constructing more roads, the result is more traffic. Instead of creating more efficient vehicules, car manufactures create larger vehicules. The network’s data traffic rises much faster than the number of internet users meaning there is growing data consumption per internet user. Our devices get more powerful, we got faster Internet, and then we build services requiring more data and computational power. This is the rebound effect. This means the gains we make in technology to reduce resource use has the opposite effect. Basically, we reduce the energy used, but we consume more.

The Internet is faster, websites are not.

Back in 2008, the median size of a web page was 530kb. Today, it's 2150kb. At the same time, While the Internet is getting faster and faster, websites are not loading faster. More images, more video, more trackers, larger scripts, more fonts (the list goes on).

Windows 95 was 30mb and today, some websites are twice this size. More and more resources are required to run digital products, powered mostly by this huge carbon-intensive infrastructure.

In his talk “The Website Obesity Crisis“, Maciej Cegłowski, founder of the bookmarking tool Pinboard, is preaching for simpler, efficient websites.

“I sometimes feel like a hippie talking to SUV owners about fuel economy.

They have all kinds of weirdly specific tricks to improve mileage. Deflate the front left tire a little bit. Put a magnet on the gas cap. Fold in the side mirrors.

Most of the talk about web performance is similarly technical, involving compression, asynchronous loading, sequencing assets, batching HTTP requests, pipelining, and minification.

All of it obscures a simpler solution.

If you're only going to the corner store, ride a bicycle.

If you're only displaying five sentences of text, use simple HTML.”

Time to design alternatives.

Around the world we are tasking designers of all fields to commit to a more sustainable route and rethink their approach from concept to delivery. Fashion designers are considering material biodegradability, product designers are considering circularity, architects are considering impacts on larger ecosystems.. it's now time for web designers and developers to consider how to build internet - in terms of resources, emissions and waste.

Designing light websites means you are making choices about what is really useful, and leaving out what's not. We've been hoarding all over the internet and so we need to ask - do we need auto play video? (Do we even need video?) Do we need 5 images of the same product? Do we need a preview of 10 next articles on every website's page? Do we need so many fonts? Does each page of a site require ten trackers? The list goes on.

Let's do a calculation to help the numbers sink in a bit, here are three websites:

- Today’s average webpage (2150kb) generates 0,6 grams of carbon dioxide each view, and for 10,000 monthly views this equals to 75kg of CO2 per year. That’s the equivalent of the a lifecycle carbon emissions of an iPhone 13 Pro Max.

- Removing a single kilobyte in a file loaded on 2 million websites reduces CO2 emissions by an estimated 2950 kg per month, the equivalent of 5 flights from Amsterdam to New York.

- Apple AirPods Pro website size is 56.77mb (26 times the size of an average website), without even counting the videos. That’s why we decided not to put a link to it.

Design choices matter, but so do those of engineering.

Here's an example of how effective coding can make a difference. "A picture is worth a thousand words," as we all know. On the Internet, this may be a lot more. Dezeen, a well-known design website, recently updated its site. Instead of high definition for everyone, they now show photos at the proper size depending on devices. This has led to enormous carbon savings, about a thousand tons per year, since it is seen by such a large audience.

Time for better and greener websites.

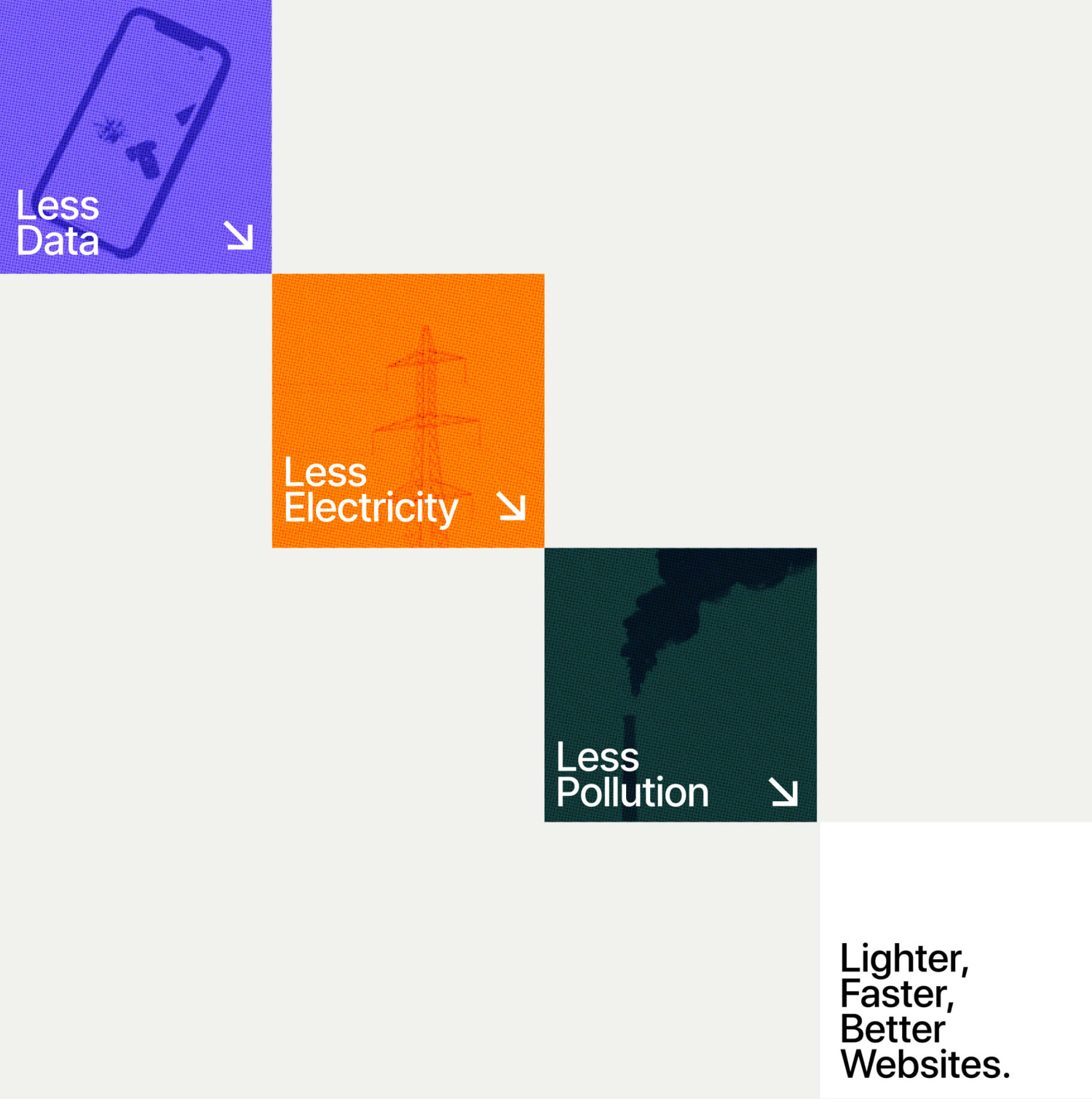

It's quite simple - making the internet more sustainable in the long run is all about producing better digital goods. And there's a huge benefit in low-websites: they are very fast (less load time = higher conversions). But on top of all these factors, one reigns supreme: how will you power your data? When you understand that renewable resources like wind and solar are up to 10 times less carbon intensive than fossil fuels, it makes a significant difference.

Websites won't save the world.

A website's overall impact is minor, as is the effect of a single plastic bag. It makes no difference if there are one or two more. Isn't it simply a plastic bag? We all know now that it's not about just one plastic bag (or one website) - it's the impact of millions of plastic bags, millions of websites. However restrictions are starting to appear for plastic, a tangible and visible material, which the bulk of the internet stays hidden (with no restrictions).

As Low-Tech Magazine is suggesting it, should we put a Speed Limit for the Internet too? "This may sound strange, but it’s a strategy we also apply quite easily to thermal comfort (lower the thermostat, dress better) or transportation (take the bike, not the car)."

In a world with boundaries, we can't grow endlessly. After all, even a cloud has its limits. Do we really need to watch The Office all over again? Probably yes. But should we do it in 4K? No.

Hey Low World.

Shaming individual behaviours isn't the way to go about it, but we can practice our individual agency - as we push for a better food system that produces healthy and fertile soil, we must do the same for the web. Actors in the digital sector should be the ones responsible for ensuring that it is sustainable by adopting practices and policies to grow an internet culture that reduces its impact on the environment, and it is as important as combatting fast fashion, intensive farming and ocean waste. Why? Because the digital products we produce do not justify the energy and carbon expenditure. On top of this the deceptive content, attention economy, advertising networks, and mass data gathering for private companies must be challenged.

All of this fits into the global storyline and our society that is so well organised around consumerism. Do we want to keep building enormous and ineffective cars? Do we require access to everything at all times, as well as bombarding viewers with huge amounts of content? Or do we begin to design better, develop better, build better, and exercise some energy restraint? Because technology and renewables alone will not save us. So for once, let's try to go Low.